The neurobiological basis for make now meaningful.

I have previously attempted to establish the case for make now meaningful, that deferring meaning into the future and thereby disconnecting it from present actions is detrimental. One of the examples I used was that of students who study for an exam (present action) in hope of getting good results (which are made known months into the future). Their neglect of effective learning in the present will likely result in failure to grow, regardless of the eventual grades achieved. Framing this in the context of reading literature, students who defer meaning to an A grade instead of continuously thinking better, using language better, hence communicating better, will make no meaning out of literature beyond a hoop that required jumping through. Possibly future meme makers who believe they learnt nothing in school.

Well, beyond reasoning and cajoling, there is a neurobiological basis for make now meaningful. I'm no biologist nor neuroscientist. I merely stand on the shoulders of giants. The giant for today is Dr Andrew Huberman. He has a wonderful podcast that you really should check out.

The pain and pleasure seesaw

Does the following sound like a familiar negotiation between adults and children, bosses and employees? “If you <insert a task that child or employee rather not do>, I will <insert reward> when you are done.”

Generally, most people don't like working hard. Some people do, but most people work hard in order to achieve some end goal. End goals are terrific and rewards are terrific whether or not they're monetary, social, or any kind. However, because of the way that dopamine relates to our perception of time, working hard at something for sake of a reward that comes afterward can make the hard work much more challenging, and make us much less likely to lean into hard work in the future. - Dr Andrew Huberman.

In one of the podcast episodes, Dr Huberman recounted an experiment conducted by Stanford University many years ago in which pre-school children drew pictures because they loved doing so. Researchers then rewarded the children with gold stars (again, sounds familiar?). Well, in a cruel twist, the researchers stopped the reward and the children became significantly less inclined to draw. This is in spite of them loving to draw even when there once was no reward. How so? Pleasure that was once more closely associated with the act of drawing was now shifted to the receipt of rewards. In Dr Huberman’s own words, “that’s just the way that these dopaminergic circuits works.”

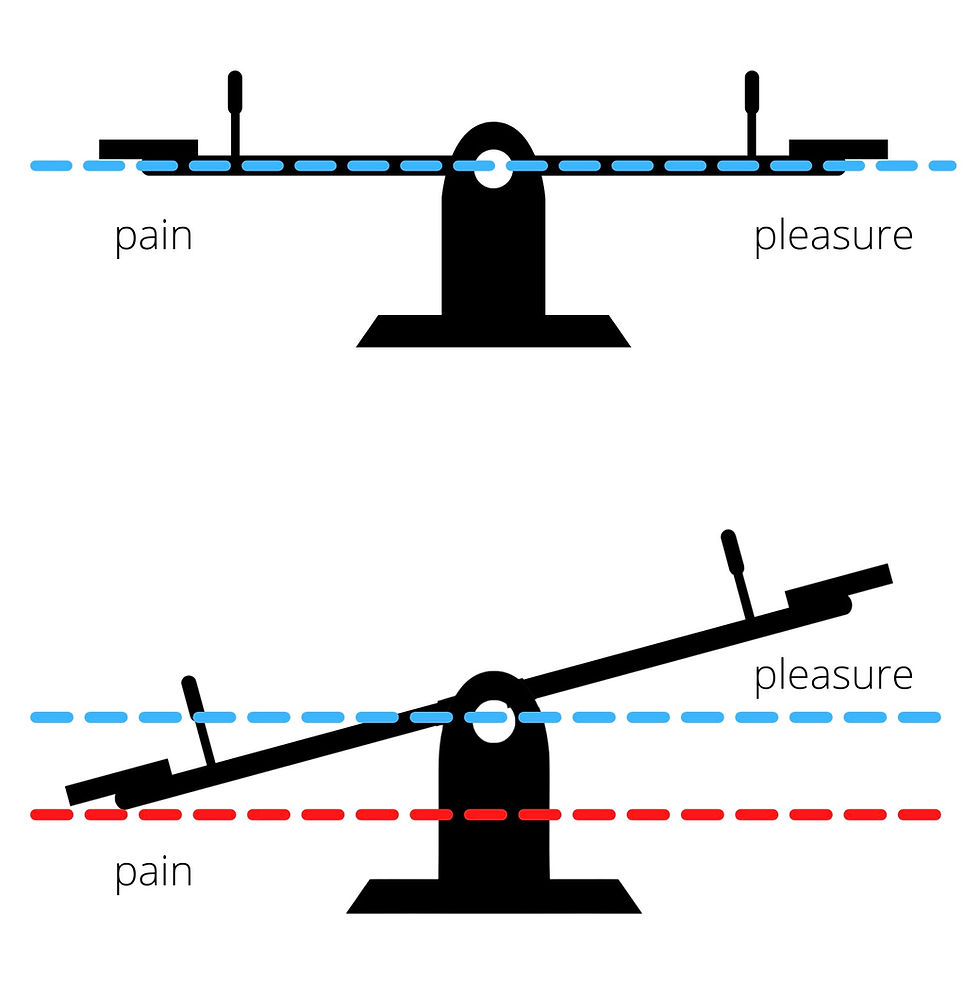

We can imagine the dopaminergic circuit as a seesaw with pain and pleasure on either side. When the seesaw is horizontal and not tilted to either side (no stimulus), this forms the baseline or tonic level of dopamine release (the blue dotted line).

The introduction of a reward will cause a spike in dopamine level because there is pleasure and the seesaw swings up on one side. Correspondingly, the pain side of the seesaw is dips below the original blue line in anticipation of a drawback when the pleasure stimulus is removed. And indeed, when the stimulus dies down as the reward is consumed, there is an experience of pain even though there isn't a pain stimulus. The new tonic dopamine level will fall below the prior level (the red dotted line) when seesaw attempts to return to a horizontal position (balancing the pain and pleasure response).

Furthermore, by deferring the reward to the end of the performance of the task, we begin to dissociate the dopaminergic circuit that would otherwise normally have been active throughout the activity. As such, by enduring the task instead of enjoying it, we build up pain (depletion of dopamine which is equivalent to depletion of energy and drive), push the eventual dopamine spike (from reward) higher than it ought to be (because it is a seesaw), which in turn causes the pain side of the seesaw to sink even further. This is the antithesis of growth mindset.

Leaning into the friction - what real life actions can I take?

The neural mechanism that governs the release of dopamine sits in the mesolimbic circuit which extends into the prefrontal cortex. This makes it possible for us to cognitively evoke dopamine release from friction or the challenge that we find ourselves in. We are able to subjectively attach dopamine release to the endeavour of our choice. What does that look like in real life?

Don't spike dopamine prior to engaging in effort and don't spike dopamine after engaging in effort. Learn to spike your dopamine from effort itself. - Dr Andrew Huberman

First and foremost, manage the rewards. Do not pile on dopamine just to get yourself started! It is not about sweetening the deal so that you can grease over the friction; you'll get diabetic on the bribes very quickly. Rewarding yourself before you even begin is a bad idea because the next time you have to get going, you will need double the reward - two coffees instead of one, or "motivational" ra-ra that needs to get louder and more intense. Also, as we have already harped on extensively, be cautious of the frequency and magnitude of the reward after the grind. That glorious holiday you have planned to reward yourself for the hard work put in for the audit is going to make the audit preparations a lot more miserable, AND the return to work after the holiday unbearably painful (sounds familiar?).

Secondly, pay attention to the seesaw. Be mindful of the intensity of both pleasure and pain. The more you indulge in pleasure, the more you accrue pain. There comes a point where the accrual of pain is so huge that persistent indulgence is no longer for pleasure but to stave off the impending pain tsunami - yes, that's the onset of addiction. The reason you binge watch K-drama or Netflix is because as the episode draws to an end, the pleasure stimulus is on the verge of being withdrawn, which means the seesaw is tilting from pleasure to pain. That little voice whispering "just one more episode" is your brain trying to prevent the tilt!

Finally, lean into the friction. Make a pact with yourself. Each day, you shall deploy five gos and five no-gos, or whichever number makes sense to you. If you catch yourself leaning away from friction, "today is not a good day to go the gym", deploy a "go" and move your butt onto the benchpress. If you find yourself reaching out for pleasure, "I deserve a snack", deploy a "no-go" and put that bag of potato chips back on the shelf. This will allow you to bring your forebrain to the fore and learn to spike your dopamine on effort and endeavours that better serve your meaning.

Comentarios